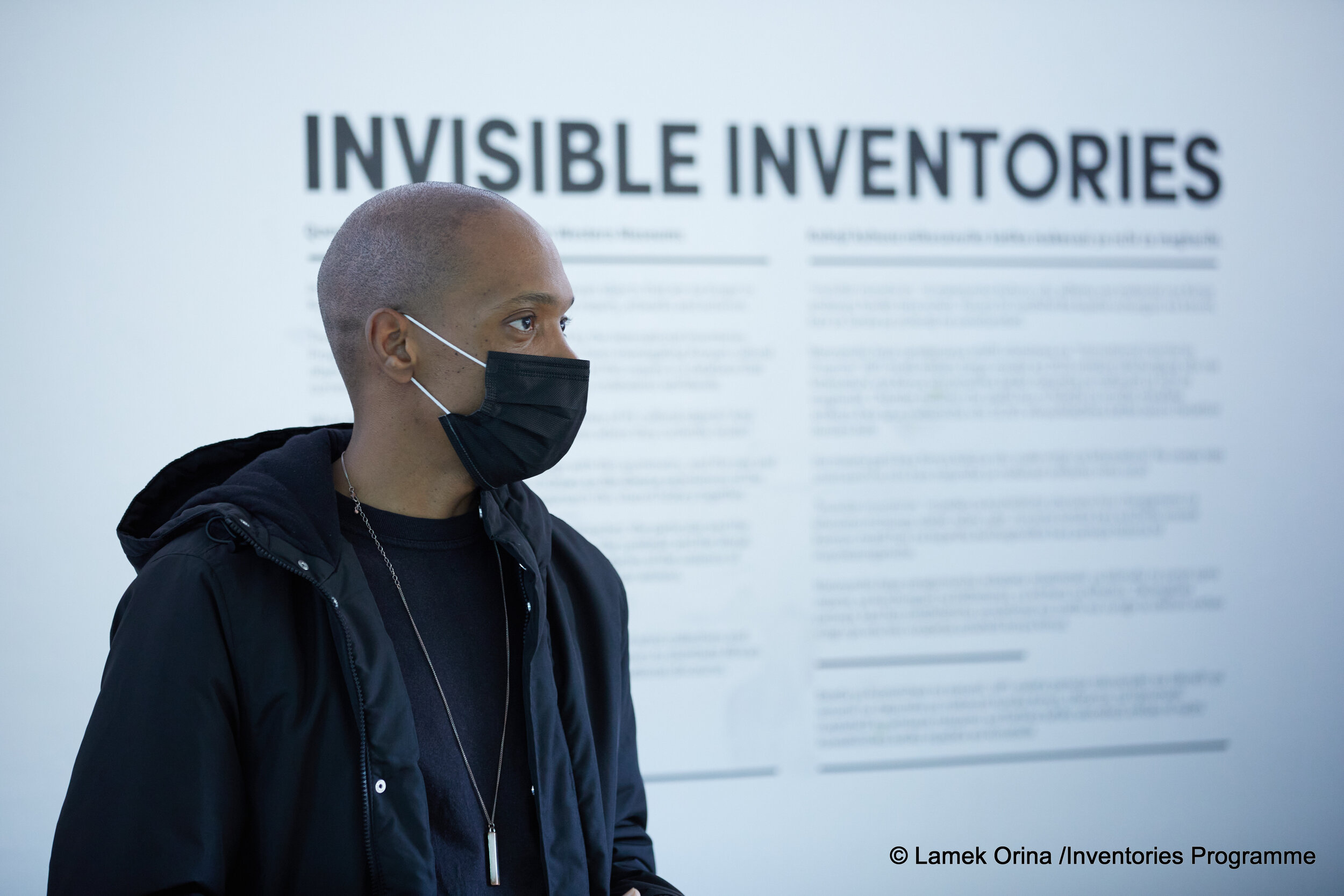

Invisible Inventories: Questioning Kenyan Collections in Western Museums—An Exhibition Series (2021)

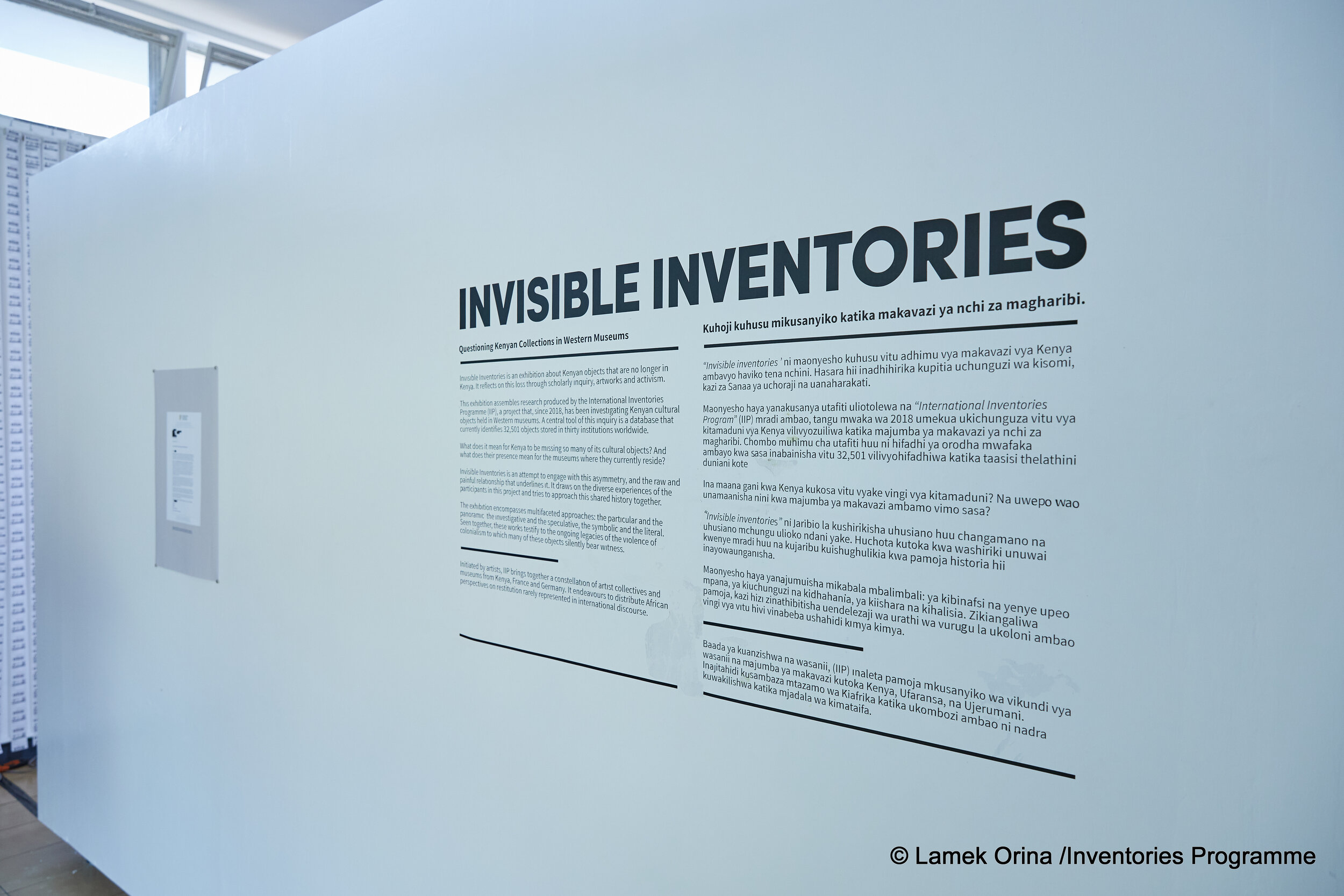

How can Kenyan cultural objects that are in the possession of cultural institutions in Europe and the US be made accessible in Kenya? This question is being investigated by the exhibition series ‘Invisible Inventories’—an exhibition project of the International Inventories Programme—which explores the questions of the objects’ absence in Kenya and reflects on this loss through art, research, inquiry and collaboration.

The exhibition series—starting in Nairobi on 17th March 2021 to 30th May 2021, proceeding to Cologne from 27th May 2021 to 29th August 2021 and concluding in Frankfurt from 5th October 2021 to 9th January 2022—is an exhibition that has been more than two years in the making!

For our contribution to the exhibition, the collective has chosen to visualize and unpack the data collected by the IIP project, a digital artefact listing 32,321 objects from 30 institutions in seven countries (as at 29th September 2020). The file’s size—a paltry 84MB—brings together a complex mix of datasets from very different organizations with a multitude of diverse internal data practices, histories, documentation values and commitments to preservation. The existence of this database therefore represents a shift in world power dynamics, which is made even more stark following the worldwide anti-racism protests of 2020. It also throws open the door to an unprecedented level of access to knowledge about the inner workings of the museums of the global North. What can this new level of access and permission bring to the table, especially for Africans?

For a Kenyan collective with Kenyan members, this is data about objects that were presumably subtracted from us as a people, even as we also consider the violence inherent in any definition of our ancestors as “Kenyans” via the drawing of arbitrary lines by a marauding gang of brutal colonialists. The effect of this subtraction on our cultural, societal and personal histories—understandably—affects how we enter these processes as arguably aggrieved parties.

Our choice to focus on visualizing the database relies on a modified version of our usual methodology, wherein we create cultural works based on the research of lived experiences. We are thus creating ways for ourselves and our publics to easily engage with, reflect on and respond to this affective data. This database isn’t the kind of conceptual research question to which we commonly apply our hive mind—it came to us simultaneously as a hyper-historical and hyper-digital object. After much consideration, we settled on the idea of engaging it as its full documentary self, and diving intentionally into its depths to see the secrets, contradictions, scandals and shadows it held within it.

The following are the pieces we made with this focus:

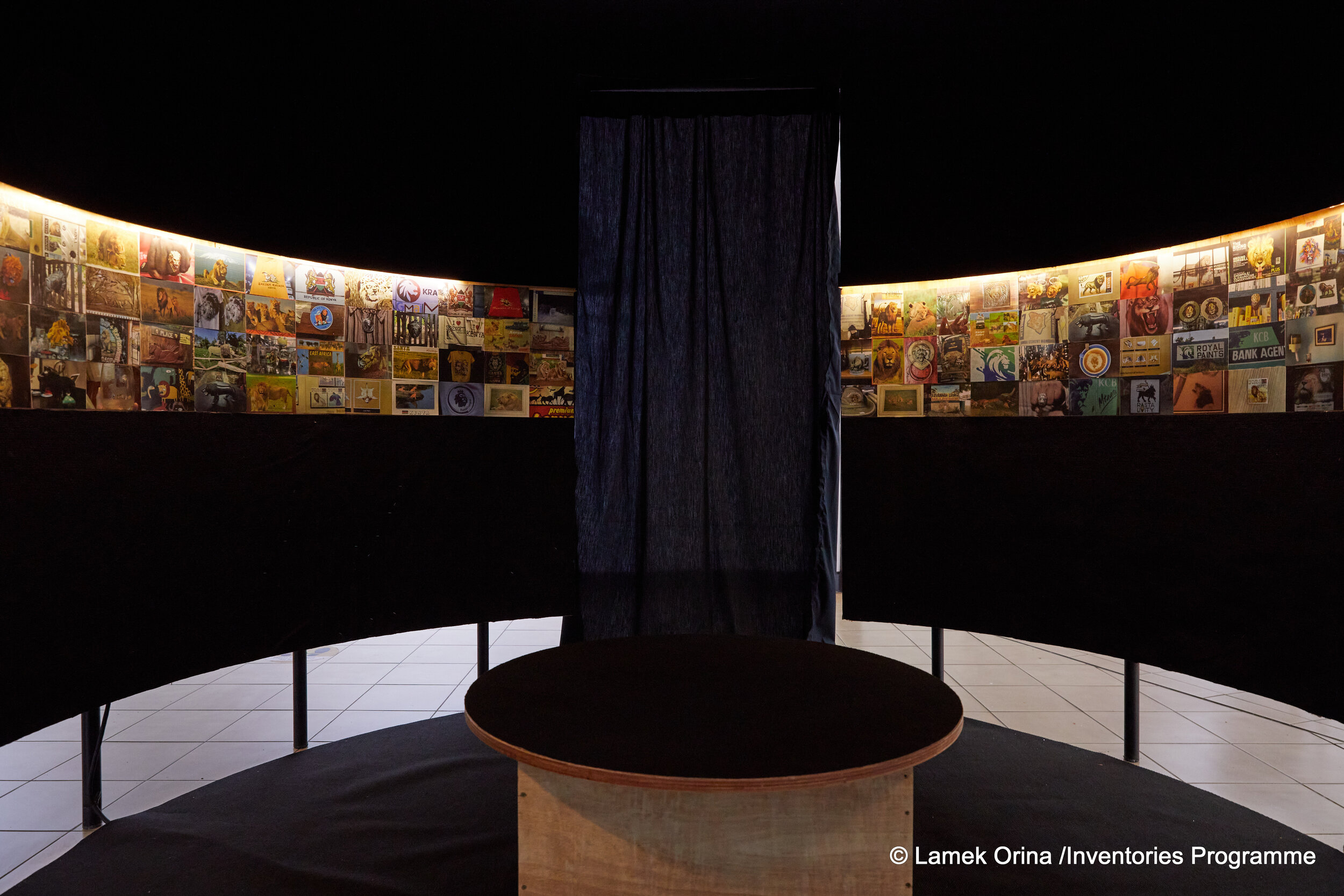

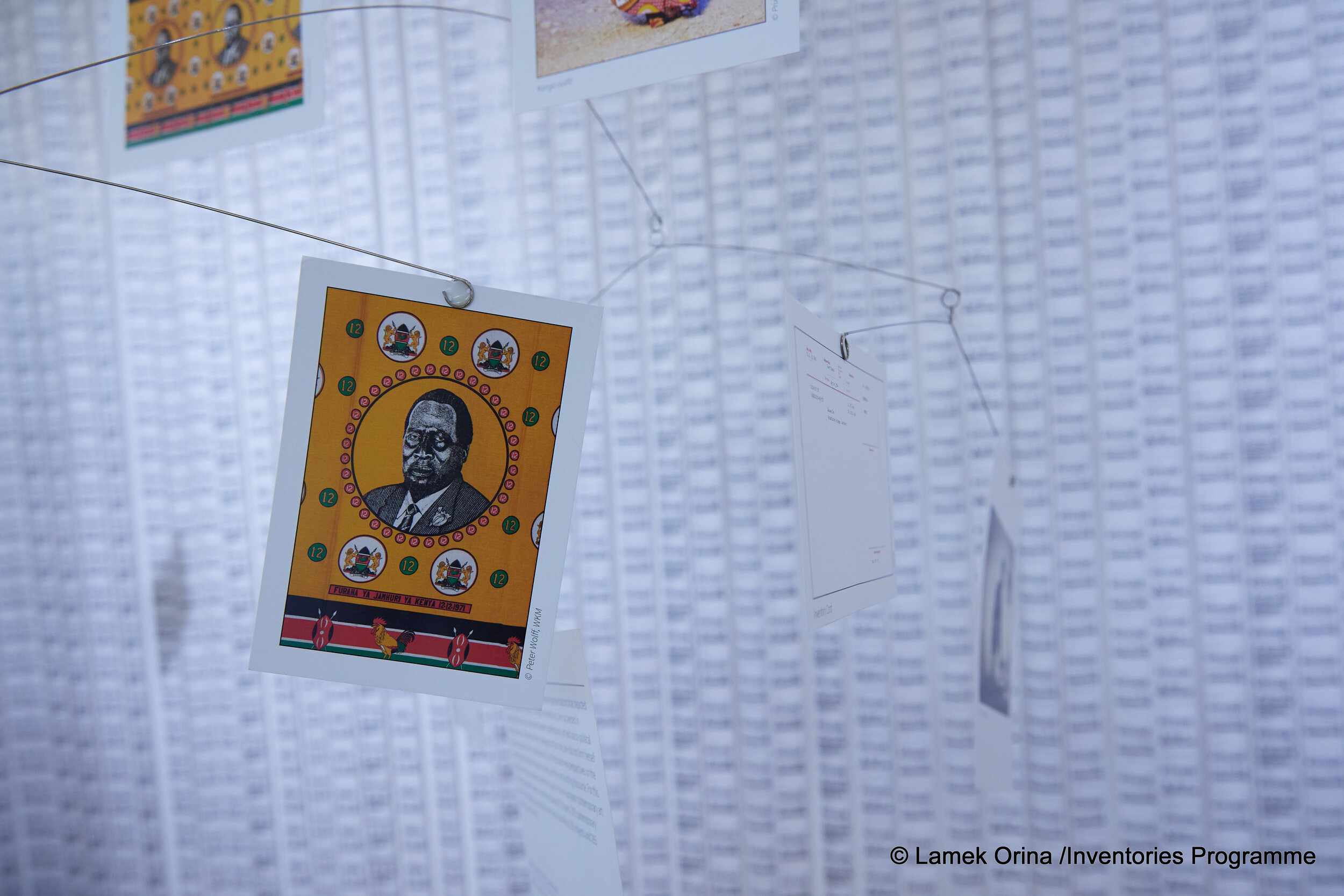

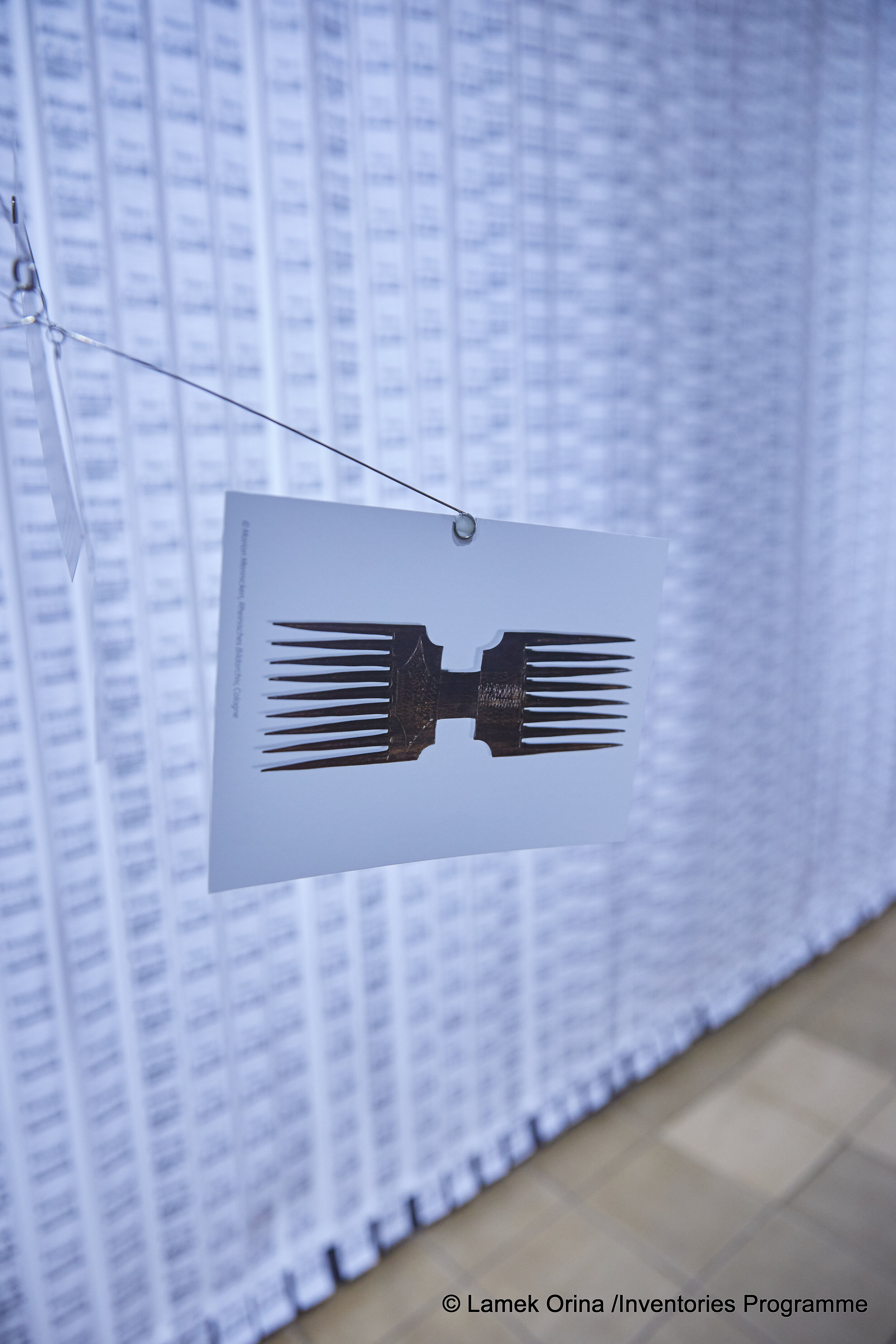

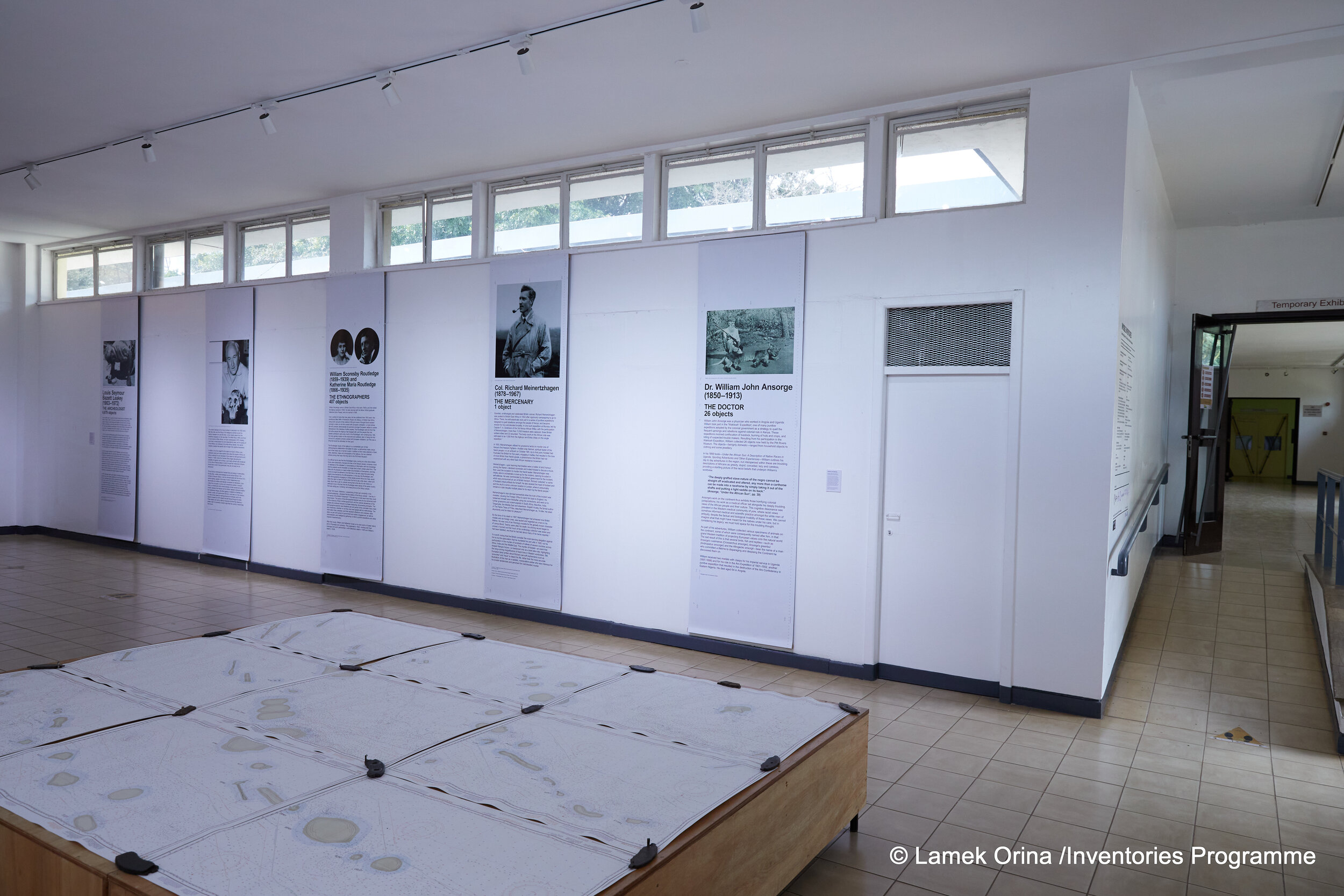

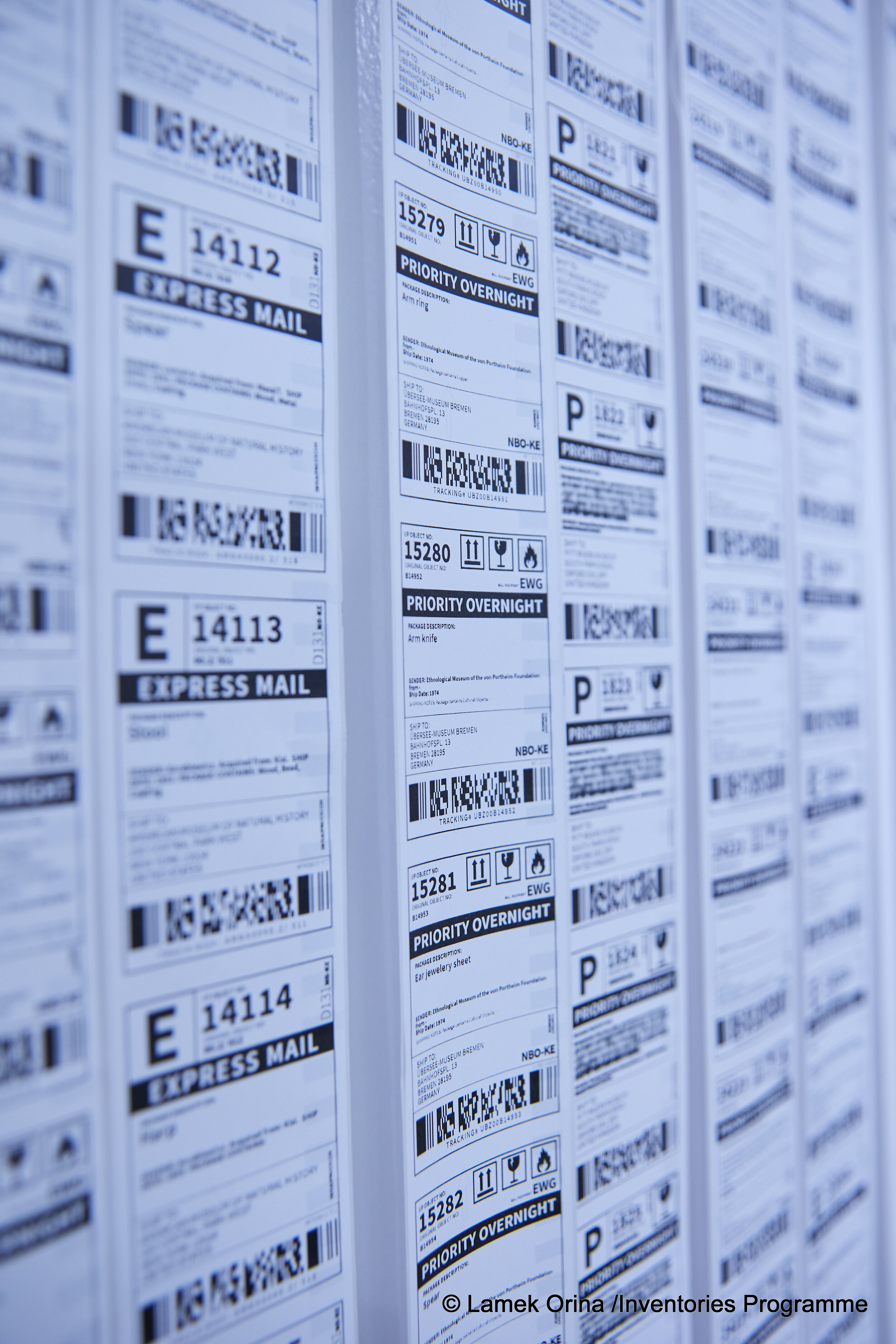

31,302 - in which we visualize the number that sits at the heart of the database activity: the total number of object records hosted in the database. We are intent on visualizing this number for the sake of keeping it in mind, and used individual shipping labels to represent each object. The gravity of this subtraction may perhaps assist audiences to really consider the scale and breadth of object movement, and the question of what it really means to take away this number of objects from a society.

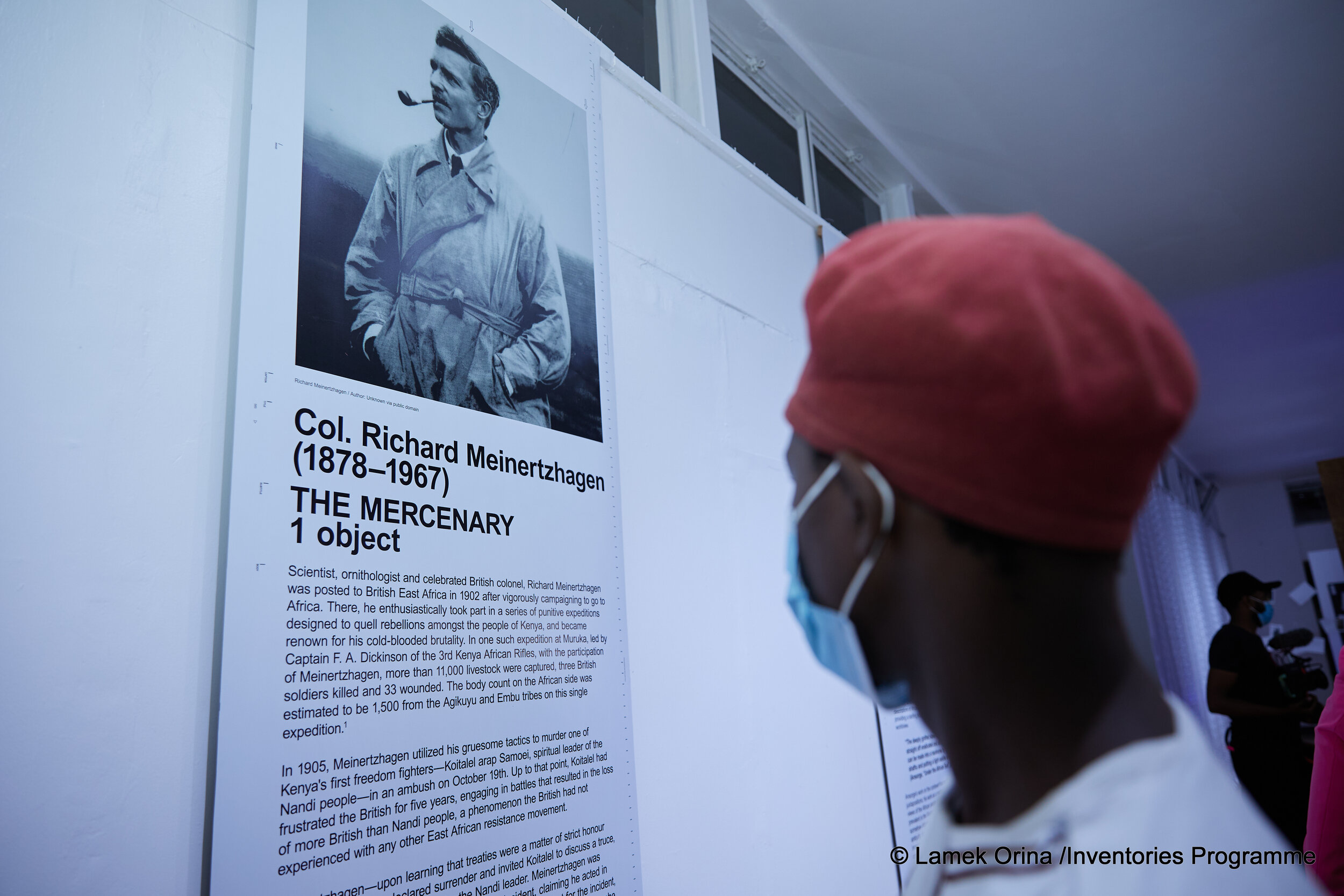

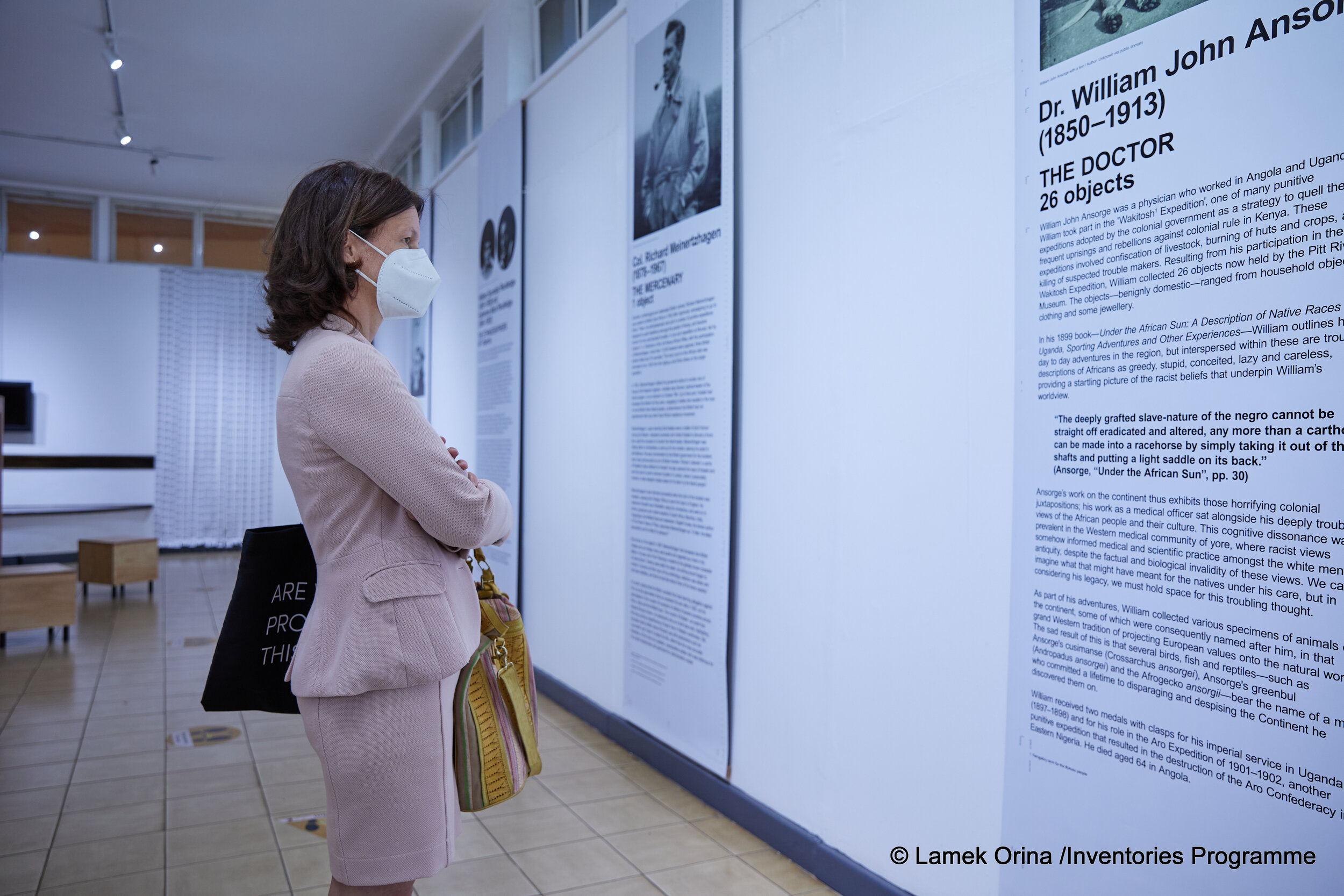

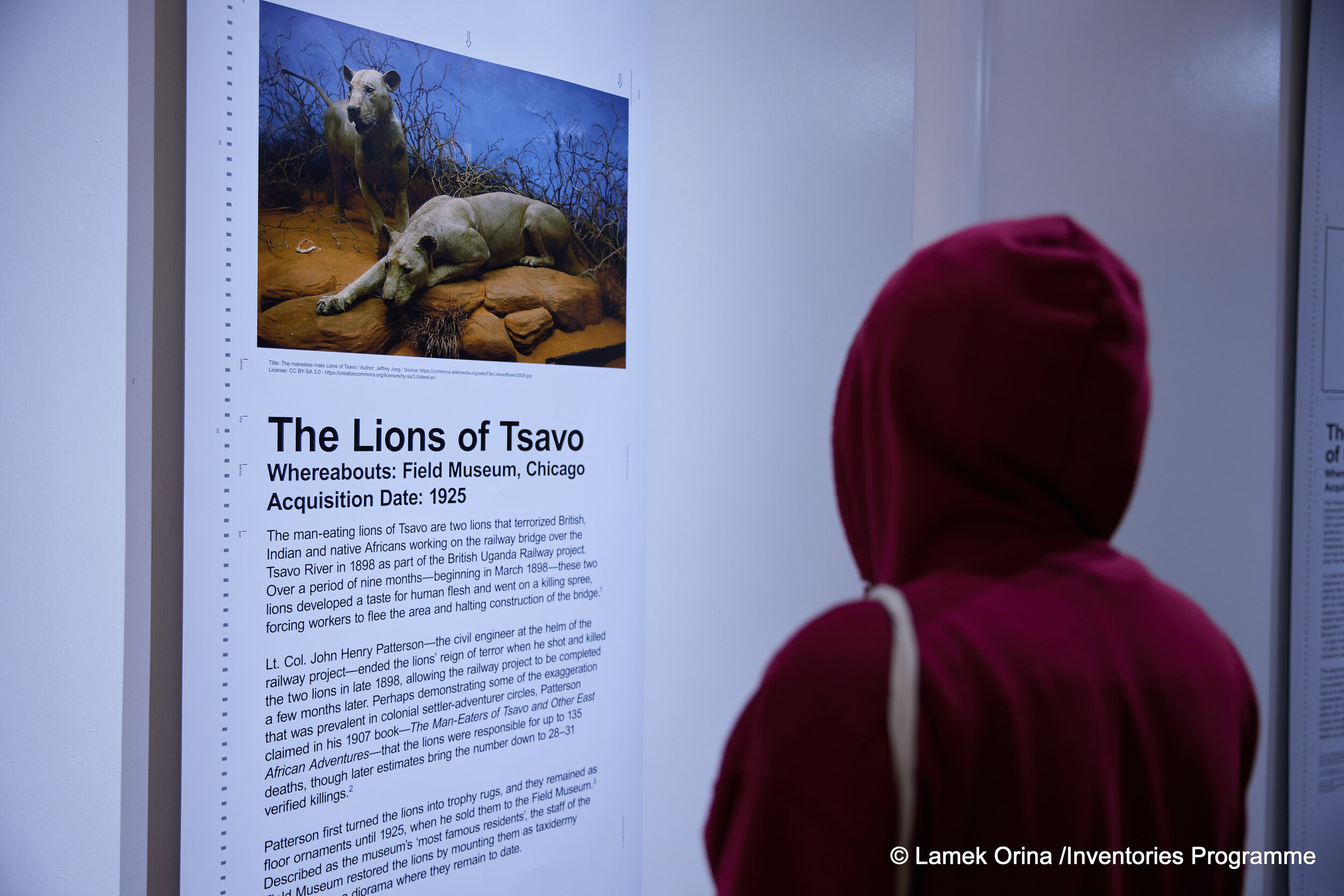

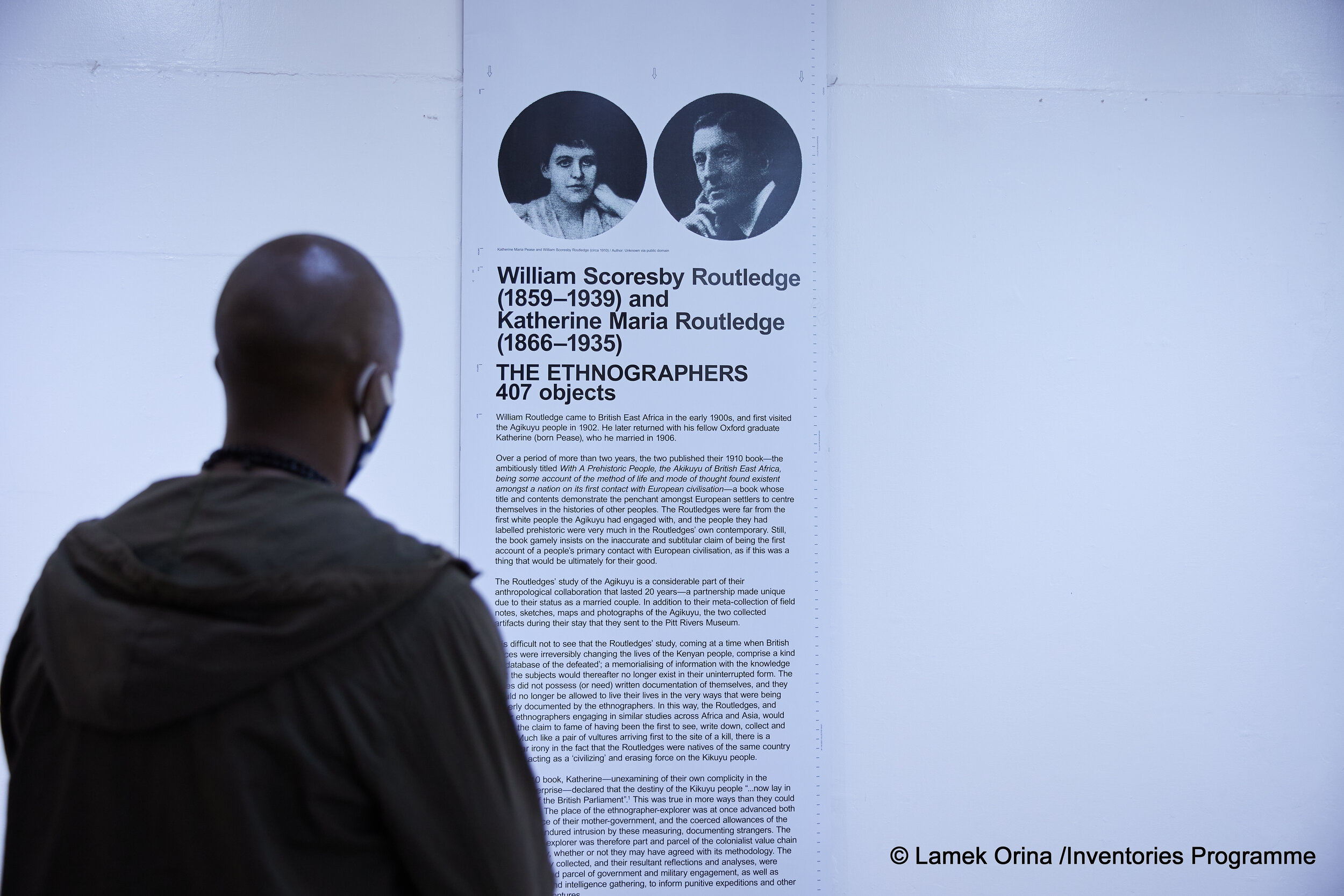

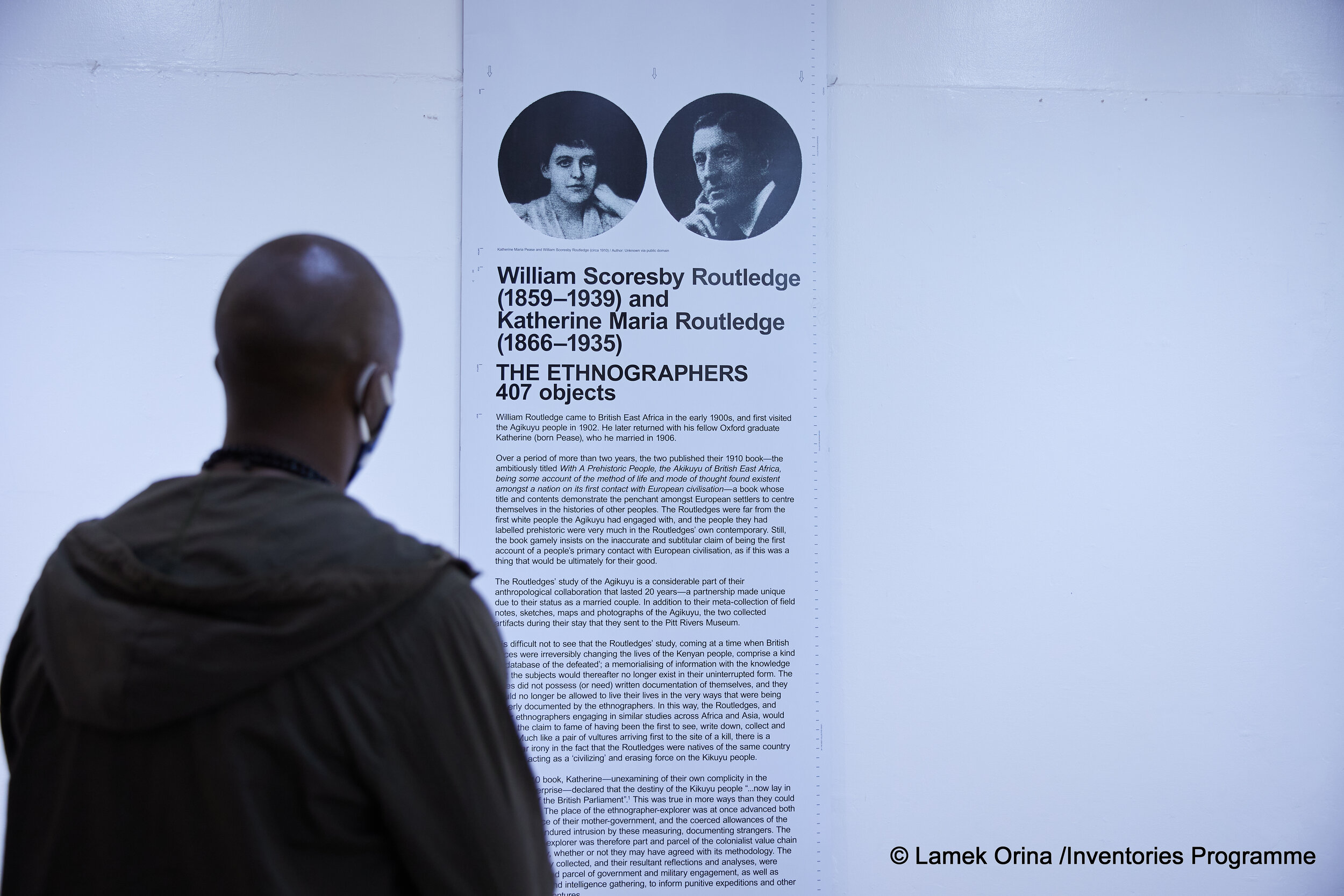

‘We Were Just Exploring’ - in which we highlight the life histories of persons named as collectors and/or donators of objects in the database (such as have been named), and consider their presence in Kenya, their object interests and how these interests shaped the ways in which Kenya is archived in museums.

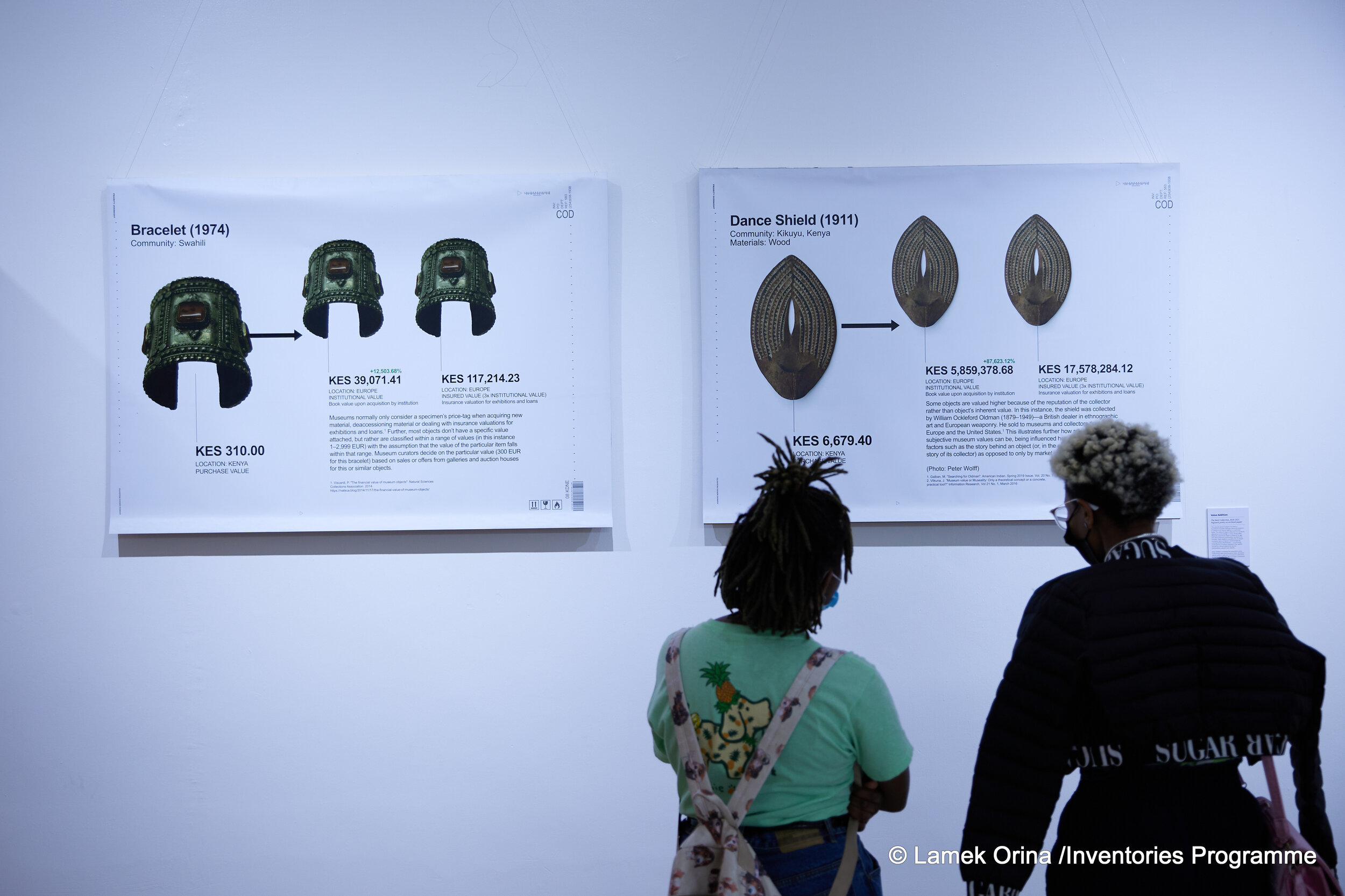

Value Addition - in which we compare the financial values of objects (acquisition price, institutional value and insurance value) and consider the effect of movement, acquisition and contemporary availability on this value.

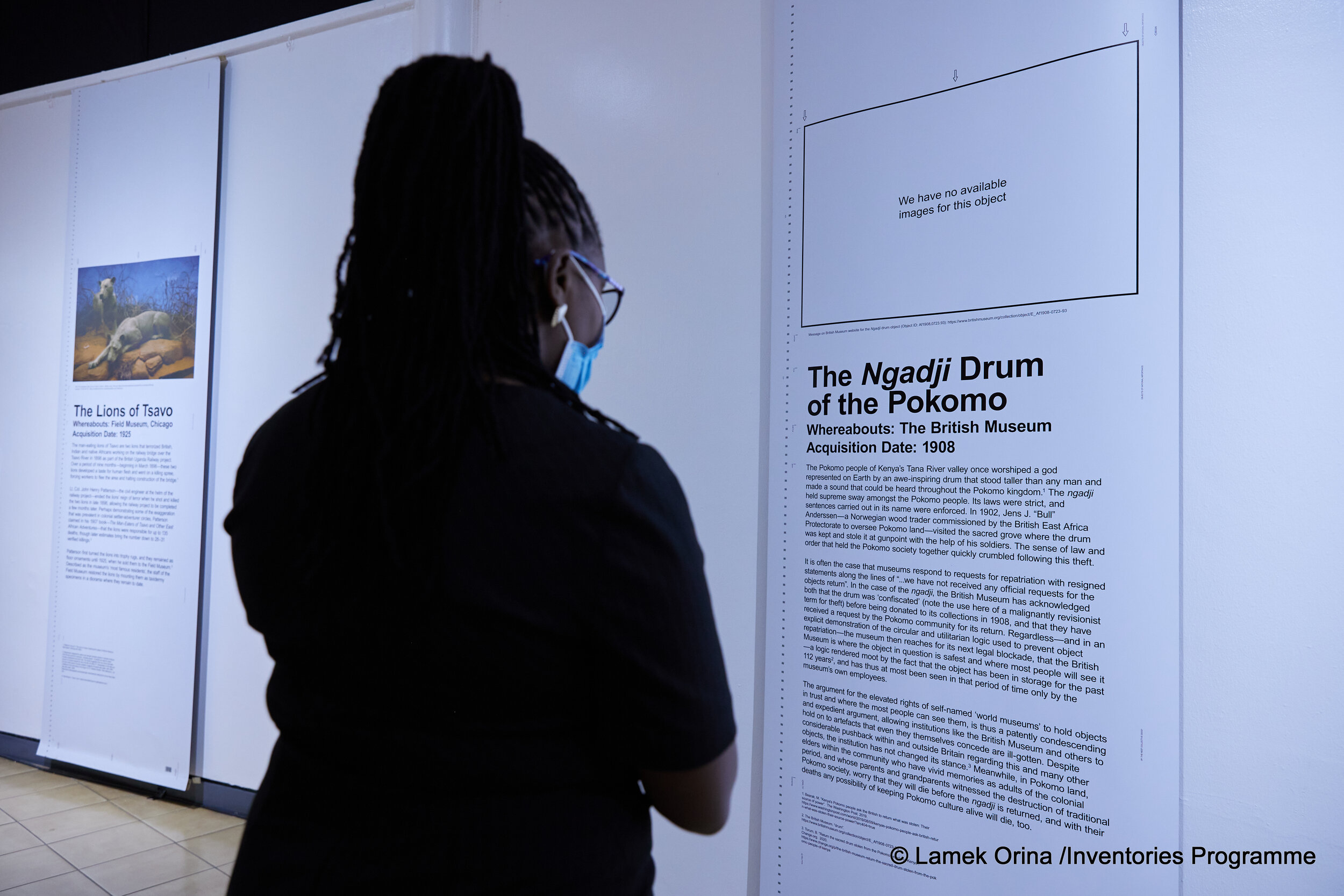

Of National Importance - in which we examine objects that have been listed as objects of national importance in presidential directives, meaning that they are objects whose repatriation the Government of Kenya is actively seeking. Two of these objects are represented in the database, both appearing in the British Museum’s collection. The first is the Kiti cha Enzi, a throne stolen by British Vice Admiral Hon. Sir E. R. Fremantle, K.C.B., C.M.G at the destruction of Witu in 1890. In a demonstration of the revisionist and malignant power of archival data, the Kiti cha Enzi is reductively listed as ‘throne’ in the British Museum archive, and the label of ‘previous owner’ of the throne disrespectfully lists the Sultan of Witu. The second of these important objects in the IIP database is the sacred Ngadji Drum of the Pokomo, which was stolen by Sir Alfred Claud Hollis in 1908 (also dismissively listed as “drum” in the British Museum archives).

Made In Kenya - in which we present findings of a study of the database records related to object materiality. What materials (e.g. wood, leather, stone, precious metals) have been used to fashion objects contained in the archives, and how are these materials spread out amongst institutions, attributed communities, years of manufacture and collection and individual collectors?

This exhibition concludes the Nest’s insightful partnership with the IIP project. We look forward to continuing our investigation into the dynamics of object movement and decolonization from a Kenyan perspective in our future research and work.